Ernest Hemingway makes 1920s Paris come alive in A Moveable Feast. Feet splash in puddles. Fires warm cafes in the Paris of December. The smell of baguettes fresh out of the oven fills the air. Copious amounts of white wine accompany dishes of oysters or fried fish.

But there’s more.

The reader also learns of Hemingway’s struggles as a writer. In a two-part post, I’m sharing six lessons I gleaned from reading A Moveable Feast, the restored edition.

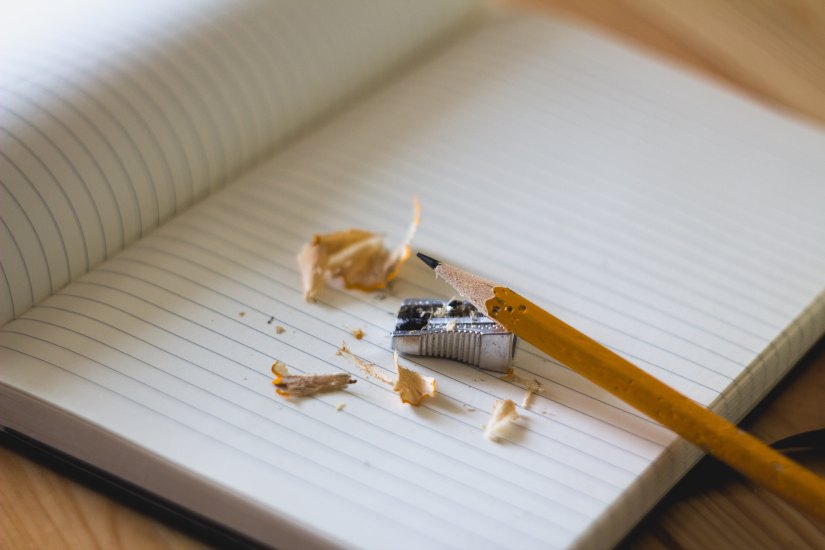

1. Writing is hard work. There are no shortcuts.

“Since I had started to break all my writing down and get rid of all facility and try to make instead of describe, writing had been wonderful to do. But it was very difficult, and I did not know how I would ever write anything as long as a novel. It often took me a full morning of work to write a paragraph.”

— Scott Fitzgerald, A Moveable Feast

Hemingway worked hard to show, rather than tell. He didn’t know whether his work was any good until he’d had a chance to examine it the next day. And there was no such thing as a one-and-done draft.

In this book, Hemingway says that he wrote the first draft of The Sun Also Rises in six weeks. Then he spent the winter of 1925 and 1926 turning it into a novel. He described it as “the most difficult job of rewriting I have ever done.”

For me, writing is a two-step process. When I write, I force my inner editor to go for a walk. And when I’m done writing, I try to let the work sit for a day or two. Only then do I invite my inner editor to sit down at my desk and begin the ruthless task of cutting, cutting and cutting some more.

I read my copy aloud. I have Microsoft Word read my work aloud. I run the text through Grammarly and frequently refer to the AP Stylebook that is always within arm’s reach. If I have time, I give the draft to my husband for yet another review. Even with all those steps, I know my work isn’t perfect. But at least I’ve put forth the effort to make it the best it can be in the time I have available.

2. Your writing process is important. Know what works best for you.

“The blue-backed notebooks, the two pencils and the pencil sharpener (a pocket knife was too wasteful), the marble-topped tables, the smell of café crèmes, the smell of early morning sweeping out and mopping and luck were all you needed. For luck you carried a horse chestnut and a rabbit’s foot in your right pocket.”

— Birth of a New School, A Moveable Feast

Hemingway’s rituals and routines got him into the writing mindset. Several years ago, I toured Hemingway’s home in Key West, Florida. The tour guide mentioned that Hemingway typically got up at about 6 a.m. to begin writing and then would work until noon. It wasn’t until after his writing day was done that he’d head to the local bar.

Unlike Hemingway, I don’t head to the local bar when I’m done writing. However, I am most productive in the early morning, preferably while everyone else in my house is asleep. I love writing while still in my pajamas, a freshly brewed cup of coffee sitting next to my laptop. My office is on the second floor, my desk faces the window. Watching the day dawn, seeing my neighbors walking with their dogs on the sidewalk below, and listening to cardinals singing their distinctive song get my creativity flowing.

My routine signals to my brain that it is time to write.

For others, the routine will be different. But knowing what works best for you goes a long way to making the most of your writing time.

3. Writers must read. A lot.

“When I was writing, it was necessary for me to read after I had written, to keep my mind from going on with the story I was working on. If you kept thinking about it, you would lose the thing that you were writing before you could go on with it the next day. It was necessary to exercise, to be tired in my body, and it was very good to make love with whom you loved.”

— Une Génération Perdue, A Moveable Feast

In almost every chapter, Hemingway mentions the books he’s reading. He also describes his visits to the legendary bookstore, Shakespeare and Company, and the generosity of its owner, Sylvia Beach. In one exchange between Hemingway and Gertrude Stein, Stein advises: “You should only read what is truly good or what is frankly bad.”

Hemingway liked to read for two reasons. First, it allowed him to take his mind off his own work. Second, he liked to read what others are writing.

Make reading the works of others part of your writing regime. The effort not only helps improve your own work, but it is also fun.

Tomorrow, I’ll share the second part of the lessons I learned from reading A Moveable Feast. If you don’t want to miss the post, please follow my blog, sign up for email alerts, or follow me on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

And you must write volumes upon volumes 🙂 Even the greatest writers have a bigger pile of rejections 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely! You made me think of this Peanuts comic:

LikeLiked by 2 people

LOL! That’s a great one !

LikeLiked by 1 person

love this – a few years ago on my old blog I’d written about this very book – https://quietradicals.wordpress.com/2016/05/13/a-virtuous-woman-hemm-on-hunger/. It really is a must read for all writers

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much for sharing a link to your post! Hemingway’s description of hunger – and of being a starving writer – also captured my attention. It really is a fantastic book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Okay, you have me interested in this book. I must seek out a copy.

I like the way you write, the photos you have inserted (is that typewriter your own? I love it!), and the clean, bright look of the blog page.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, the typewriter is mine! It belonged to my dad. It got him through college.

Thanks so much for the compliment. 😊 The book is great. And it is one of those that is easy to read in short bursts. I read a chapter and then would ponder it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hearing that makes it all the more appealing. I love books that can easily be read in short bursts, my quiet time for reading being a rarity.

LikeLiked by 1 person